- Who gets Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (the “typical” patients)?

- Classic symptoms of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

- What causes Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis?

- How is Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis diagnosed?

- Treatment and Course of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

- What’s new in Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis?

- In medical terms, by David Hellmann, M.D.

Who gets Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis?

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis is nearly equally distributed between the sexes, with a slight male predominance. Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis typically occurs in middle age, but is found in people of all ages. Although it is unusual for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis to occur in childhood, it is not unusual for a Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis patient to be in his/her 70s or even 80s at the time of diagnosis.

Pictured below is a chest x–ray showing bilateral lung nodules in a 27 year old Indian man with Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis.

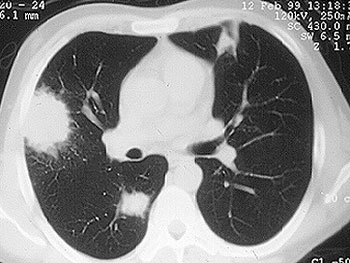

Pictured below is a CT scan from the same patient. The view is a cross–section through the patient’s lungs. The CT scan not only permits a better appreciation of the lesions’ size, it also detects more lesions.

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis can affect virtually any site in the body, but it has a predisposition for certain organs. The classic organs involved in Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis are the upper respiratory tract (sinuses, nose, ears, and trachea [the “windpipe”]), the lungs, and the kidneys. Listed below are the organs commonly involved in Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis and the specific disease manifestation(s) in each organ.

Ear

Ear infections that are slow to resolve. Recurrent otitis media. Decrease in hearing.

Eye

Inflammation can occur in different parts of the eye. Inflammation in the white part of the eye is known as the sclera (“scleritis”). “Uveitis” is inflammation within the eye. Inflammation behind the eye is known as an “orbital pseudotumor”. An orbital pseudotumor such as those caused by Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis can cause “proptosis”, or protrusion of one eye.

Pictured below is a computed tomography (CAT) scan of the eyes in a patient with a retro–orbital mass (a mass behind the eye) in a man with Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Masses such as these sometimes cause an abrupt loss of vision through stretching or compression of the optic nerve, which enters the back of the eye.

Nose

Nasal crusting and frequent nosebleeds can occur. Erosion and perforation of the nasal septum. The bridge of the nose can collapse resulting in a “saddle–nose deformity”. Pictured below is an example of this deformity before and after cosmetic surgery. This resulted from the collapse of the nasal septum caused by cartilage inflammation. This patient has Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis, but an identical lesion may occur in Relapsing Polychondritis.

Sinuses

Chronic sinus inflammation that sometimes leads to a destructive process of tissues around the sinuses.

Trachea

A characteristic respiratory tract complication of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis: narrowing of the “windpipe” just below the vocal cords, a condition called “subglottic stenosis”. This narrowing, caused by inflammation and scarring, causes difficulty breathing and may, after a subacute progression, necessitate emergency tracheostomy. Pictured below are two figures that show subglottic stenosis before (left) and after (right) surgery, performed by an Ear, Nose, & Throat specialist. The surgery provided dramatic improvement in the patient’s breathing.

Lungs

A pneumonia–like syndrome, with lung “infiltrates“ can be seen on chest x–ray. Bleeding from the lungs can occur.

Kidney

Inflammation can occur in the kidney, leading to small (or rarely, large) amounts of blood and protein in the urine. This condition is called glomerulonephritis. If not treated aggressively, Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis’s involvement of the kidneys can lead to kidney failure. Renal masses can occur, but are very unusual in this disease.

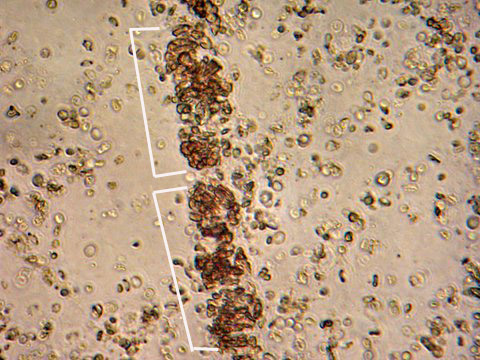

The image below is from a urinalysis of a patient with kidney inflammation. When Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis is active, red blood cells will form a clump or “cast” (bracketed in white) within the tubules of inflamed kidneys. These “casts” pass through the renal system and may be viewed under the microscope in a patient’s urine.

Skin

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis can cause many kinds of skin rashes. The most common rash occurs in the form of small purple or red dots on the lower extremities (known as “palpable purpura”). Inadequate blood flow to fingers and toes can lead to Raynaud’s phenomenon (extreme sensitivity of the fingers to cold) and even infarctions of the tips of fingers and toes, with the development of gangrene.

Joints

Arthritis can occur, with joint swelling and pain.

Nerves

Peripheral nerve involvement leads to numbness, tingling, shooting pains in the extremities, and sometimes to weakness in a foot, hand, arm, or leg.

Miscellaneous

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis involvement of nearly all organs has been described, including the meninges (the layers of protective tissue around the brain and spinal cord), the prostate gland, and the genito–urinary tract. In addition to involving specific organs, Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis also commonly results in generalized symptoms of fatigue, low–grade fever, and weight loss.

The cause of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis is not known. Compared to diseases with obvious genetic predispositions, genetics appear to play a relatively small role in the etiology of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis . It is very unusual for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis to occur in two people in the same family. (It is possible, however, that less obvious genetic risk factors exist, e.g. genes that might pre-–dispose a patient to infection with an etiologic organism). For some time, an infection has been suspected of causing (or at least contributing to) Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis , but no specific infection (bacterial, viral, fungal, or other) has been identified.

How is Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis Diagnosed?

Whenever possible, it is important to confirm the diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis by biopsying an involved organ and finding the pathologic features of this disease under the microscope. Because many diseases may mimic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (and vice versa), before starting a treatment regimen it is essential to be as certain of the diagnosis as possible. We discuss some of the specific biopsy procedures used to diagnose Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis in the section of this Websie entitled What is Vasculitis: Diagnosis?.

Because Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis so often involves the upper respiratory tract (sinuses, nose, ears, and trachea [“windpipe”]) and because biopsy of these tissues is a relatively non–invasive procedure, these sites are frequently biopsied in patients suspected of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis . Unfortunately, the yield of biopsies from these sites is rather low: probably less than 50%. Therefore, sometimes more invasive procedures are required to make the diagnosis.

Lung biopsy (either open or thoracoscopic) is often the best way of diagnosing Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis . The ample amount of tissue obtainable through these procedures usually permits confirmation of the Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis diagnosis. Similarly, although the amount of tissue obtained through a kidney biopsy is usually much smaller, the finding of certain pathologic features in the context of a patient’s overall symptoms, signs, and laboratory tests is frequently diagnostic.

Since 1982, when ANCAs (anti–neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies) were first described, the role of these antibodies in the diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis has grown. ANCA testing, which involves the performance of a simple blood test, has achieved wide availability during the 1990s. This is both good and bad: use of ANCA tests has led to earlier diagnoses and more rapid institution of appropriate treatment in many cases, but has also resulted in misdiagnosis and incorrect treatment when the tests are not performed or interpreted correctly.

As their name implies, ANCAs are directed against the cytoplasm (the non-nucleus part) of white blood cells. Their precise role in the disease process remains uncertain but is a topic of considerable research interest. ANCAs come in two primary forms: 1) the C–ANCA [C stands for cytoplasmic] and, 2) the P–ANCA [P stands for perinuclear]. C–ANCAs have a particularly strong connection to Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (up to 80% of patients — and possibly more of those with active disease — have these antibodies). When C–ANCAs are present in the blood of a patient whose symptoms or signs suggest Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis , the likelihood of the diagnosis increases considerably. In most cases, however, it is still VERY IMPORTANT to biopsy an involved organ to verify the diagnosis.

Treatment and Course of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Until the 1970s, Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis was nearly always a fatal condition. The use of prednisone and other steroids helped prolong patients’ lives, but most patients eventually succumbed to the disease within a few months or years. The first use of cyclophosphamide in the late 1960s began to change the terrible prognosis of this disease. Using the combination of cyclophosphamide and prednisone, more than 90% of patients with severe disease respond to treatment, and 75% are able to achieve disease remissions. Unfortunately, Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis is a disease in which relapses frequently occur. Approximately half of all patients who achieve disease remissions eventually suffer recurrences (“flares”). Flares of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis are usually responsive to the same treatment that induced remission, but sometimes intensification of treatment (for example, changing to a more powerful medication) is required.

During the 1990s, physicians have increasingly used the combination of methotrexate and prednisone rather than cyclophosphamide and prednisone for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis patients who do not have immediately life-threatening disease (particularly disease that does not involve the kidneys severely), because of the frequency of severe side-effects associated with the latter regimen.

Bactrim (or Septra), a combination of two antibiotics (trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole) may also be helpful in the treatment of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis , particularly in patients whose disease is limited primarily to the upper respiratory tract. A large, multi-center study demonstrated that Bactrim is useful in preventing flares of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis in the upper respiratory tract.

What’s New in Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis?

In the past few years, significant advances have been made in understanding Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis , although many important questions remain. In addition to an improved understanding of how to use the currently available medicines for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis , it is likely that the next few years will witness the development of new medicines for this disease. Scientific breakthroughs may lead to the design of more specific modulators of the immune system that are of great benefit to patients with Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis .

In medical terms, by David Hellmann, M.D.

A discussion of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis written in medical terms by David Hellmann, M.D. (F.A.C.P.), The Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center, for the Rheumatology Section of the Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program published and copyrighted by the American College of Physicians (Edition 11, 1998). The American College of Physicians has given us permission to make this information available to patients contacting our Website

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis is a disease involving granulomatous inflammation, necrosis and vasculitis that most frequently targets the upper respiratory tract, lower respiratory tract, and kidneys. Although Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis can begin at any age, the average age of onset is about 40 years. Other organs frequently affected by Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis granulomatosis include the eye (proptosis and double-vision from retro-orbital pseudotumor, scleritis), skin (ulcers, purpura). or peripheral nerve (mononeuritis multiplex). Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis may be limited to one site for many months or years before disseminating. Systemic symptoms (fever, fatigue, weight loss) are also common. Anemia, mild leukocytosis, and elevated Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are nonspecific laboratory findings. Chest radiographs often show infiltrates, nodules, masses, or cavities; only hilar adenopathy is incompatible with the diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. CT of the chest is more sensitive than chest radiography and can be abnormal when the chest radiograph is negative. Glomerulonephritis causes hematuria, erythrocyte casts, and proteinuria.

A novel group of autoantibodies, ANCAs, helps support the diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis and related forms of vasculitis and gives insight into the pathogenesis of these diseases. ANCAs are directed against enzymes cantained in primary granules of neutrophils and monocytes. Two main types of ANCAs are recognized. The C-ANCAs are directed against serine proteinase 3 and are relatively sensitive and highly specific for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. The P-ANCAs are directed against myeloperoxidase and other antigens and are not specific for any single form of vasculitis, but have been seen in some patients with Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa, Churg-Strauss vasculitis, and some forms of pauci-immune glomerulonephritis (referred to as microscopic polyarteritis nodosa). Some patients with pulmonary-renal syndromes that may not fit the critieria for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis are also seropositive for ANCAs. Some patients with inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or SLE may have atypical P-ANCA test results, based on the autoantibodies directed against other neutrophil constituents such as lactoferrin.

ANCAs may be not only markers for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis and related disorders, but they may also be actors in pathogenesis. Studies show that when neutrophils are exposed to cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor, small amounts of serine proteinase and myeloperoxidase, the targets for ANCAs, are expressed on the surface of neutrophils. Adding ANCAs to these cytokine-primed neutrophils causes them to generate oxygen radicals and release enzymes capable of damaging blood vessels.

The diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis is established most securely by biopsy specimens showing the triad of vasculitis, granulomata, and large areas of necrosis (known as geographic necrosis) admixed with acute and chronic inflammatory cells. Only large sections of lung tissue obtained via thoracoscopic or open lung biopsy are likely to show all of the histologic features. However, more easily obtained biopsy specimens of the nose, or sinuses may show several of the changes that are highly suggestive of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Such a biopsy specimen combined with a compatible clinical picture and seropositivity for C-ANCAs should suffice to secure the diagnosis. Seropositivity for C-ANCAs alone is not specific enough to establish the diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis.

Untreated Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis is fatal. Prednisone may slow progression of the disease but by itself is insufficient to arrest the disease. Respiratory tract disease usually progresses slowly, but renal disease can progress rapidly and therefore warrants urgent evaluation and treatment. With the traditional treatment of prednisone (initiated at 1 mg/kg daily for 1 to 2 months. then tapered) and cyclophosphamide (2mg/kg daily for at least 12 months), more than 90% of patients improve and 75% remit. However, 50% of the patients who later remit also relapse, and oral daily cyclophosphamide causes serious toxicity. Short-term toxicity includes cytopenia, infection, and hemorrhagic cystitis. Long-term use of cyclophosphamide in patients with Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis more than doubles the risk of cancer overall, increases the risk of bladder cancer 33-fold and the risk of lymphoma 11-fold. Monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide appears less toxic but also less effective. Weekly, methotrexate appears to be an effective alternative for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis that is not immediately life-threatening, and it also appears to be beneficial in maintaining remission. The role of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in treating active disease is controversial, with some finding it effective for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis limited to the respiratory tract, and others not. In patients who have achieved remission, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole reduces the relapse rate.